When the first major Lowell textile mills began operating in

1823, corporation owners hired unmarried New England farm women between the

ages of 15 and 30 to work in the factories. The corporations offered these

women good housing, moral supervision, cultural opportunities, steady work and

regular pay.

Women came to Lowell for a variety of reasons: from severe

economic hardship to a desire for personal independence. They were expecting to

stay here for only a few years before returning to their rural farmsteads. The

founders of Lowell intended to create an industrial system without a permanent

working class.

Once here, the women found life in Lowell far more

stimulating than anything they had previously experienced. They discovered a

fast-growing city. They struck up friendships with each other. They earned

money of their own and had opportunities to spend it.

The women were proud to call themselves “mill girls”. They

witnessed visits by President Andrew Jackson and other dignitaries from around

the world. Although the working day was long and tedious, the factories were

the most modern anywhere. Lowell was considered America’s city of the future.

Success spawned competition: new mill towns with new

machinery and new power systems. Lowell owners responded by increasing

workloads, cutting wages, and raising rents in boardinghouses. In turn, the

women initiated strikes during the 1830's. A decade later, they spearheaded a

well-organized movement for a 10-hour workday.

By mid-century Lowell had lost its magic. Owners found it

more difficult to recruit Yankee women, and Irish immigrants began to take jobs

in the mills. After the Civil War, other immigrant groups came here to work. By

the turn of the century, few Yankee “mill girls” remained in Lowell.

TIME TABLE

Arranged to make working time 66 hours per week. Standard

time was always marked at noon.

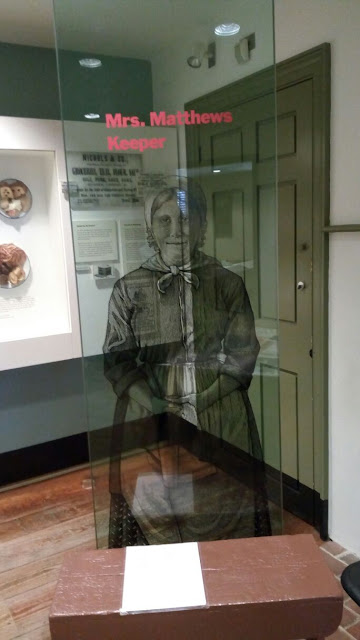

THE BOARDINGHOUSE UNIT

During the middle of the 19th century there were

approximately 70 corporation-owned boardinghouse blocks for factory workers in

Lowell. Most units housed only female workers.

Some were reserved for male employees-machinists, carpenters, manufacturers

and watchmen. In a few instances, both men and women lived in a single

boardinghouse.

This unit consisted of four floors. The second and third

floors each contained three bedrooms. The fourth floor was a garret where the

women slept dormitory style. Privies, storage sheds, and a laundry room were

located in the backyard.

FOODWAYS

The boardinghouse keeper provided factory women with three

full meals a day on a tight schedule established by the mill owners. Because

her income from tenants was limited, the keeper hoped her “bill of fare” would

attract additional boarders to supplement her livelihood. As a result, food

planning, preparation, and service was the most important as well as the most

time-consuming tasks she performed daily.

Factory women needed hearty meals to sustain them during

long hours in the mills. Meals were high in calories and heavy in fats, with

some form of meat or fish served three times daily. Afternoon dinner was the

main meal, both in food quantity and preparation time.

BOARDINGHOUSE KEEPER:

DAILY TASKS

Sound

morning wake up; Light stove and tend; Sweep common areas of house; Serve

breakfast/dinner/supper; Wash dishes from meals; Light lamps; Dispose of ash

from stoves; Monitor behavior of boarders; Supervise children; Clear dishes

after meals.

WEEKLY

TASKS

Update lists

of boarders; Report any changes to corporation; Launder bed linens for boarders

and their families; Order Foodstuffs; Stitch hems on sheets and other household

linens; Plan menus; Launder clothes for boarders and their families; Inventory

supplies and equipment, order as needed.

Ann Sweet Appleton

“Mill Girl,” 1847

“Another pay

day has come around. I earned 14 dollars and a half, nine and a half dollars

beside my board. The folks think I get along first rate, they say. I like it as

well as ever and Sarah don’t I feel independent of everyone! The fact that I am

living on no one is a happy one indeed.”

Nice job Ruth. Now you will have to read Lucy Larcum's autobiography, as she too was a Mill Girl. The founders of Lowell and Lawrence were idealistic, thinking that the work at the mills would be temporarily staffed by people, men and women, looking for a few years off the farm. Lucy Larcum became a Mill Girl after her father died and left he mother with little money and a family of children to care for. Lucy did leave the mills, and went west to teach in a one room schoolhouse in Illinois. She later returned to Massachusetts and taught at what is now Wheaton College, and she became an editor of a few journals. Sadly, most mill girls stayed mill girls, especially the later one who were immigrants.

ReplyDeleteI really liked the tour, and I saw a picture of Lucy Larcum there too. She had some writings at the house as well. Can I have the book next week if you still have them?

DeleteHi Ruth, Sorry I did not bring in a copy of the book. You can read it online on Google Books. Here is the link:

Deletehttps://books.google.com/books/about/A_New_England_Girlhood_Outlined_from_Mem.html?id=SMQ2AAAAMAAJ